Cooperative Listening Devices with Distributed and Wearable Microphone Arrays

I was fortunate enough to spend two summers (‘18 & ‘19) as a research assistant in the lab of Ryan Corey, PhD. When I was working with him, he was a doctoral candidate in Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. This post summarizes our work.

Introduction

Hearing aids don’t work well in noisy, reverberant environments where lots of people are talking at once (e.g. a crowded bar, conference poster session, etc.). Ryan, a hearing aid user himself, devoted his entire Ph.D. to improving the performance of hearing aids in noisy environments. In doing this, he also helped to develop what he calls ‘augmented listening (AL)’ technologies. You can read more about augmented listening technologies here, but in general, they can be grouped into four categories of products:

- traditional hearing aids

- personal sound amplification products (PSAPs)

- smart headphones, or “hearables”

- virtual, augmented, and mixed reality headsets

Much of Ryan’s work, where the primarily application is traditional hearing aids, can be readily extended to these other AL technologies.

Real-World Sound De-mixing and Re-mixing

In an ideal world, a hearing aid user could turn up the volume of a particular sound source (a person they are conversing with) and turn down the volume of background noise (mechanical noise, other people talking, loud music, etc.). A perfect AL system would work like a mixing board in a recording studio: each sound source would have its own slider, and the user — or an algorithm — would decide how much of each source should end up in the final mix.

Developing such a system is not a trivial task, as you might imagine. The system would have to continuously do the following, in real-time:

- Identify all sources of sound in a given environment

- Identify the types of sounds that are coming from each source

- Separate the sounds into their own channels

- Apply appropriate equalization and dynamic range compression settings to make the sounds more ‘listenable’

- Allow the user to adjust the gain of each source while preserving each sources’ spatial cues

Source separation itself is a super difficult problem, but doing it in real-time for human listening (as opposed to machine listening) applications requires only a few milliseconds of delay between the microphone and the ear, making the problem orders of magnitude more difficult. Luckily, AL technologies are not constrained by having only two ears, the way humans are. We can use dozens or even hundreds of microphones (microphone arrays) to learn about a given auditory scene and process it accordingly.

Microphone Arrays

Though we may not think about it, we are constantly surrounded by microphones (see ‘A Word on Privacy’ section if this freaks you out as much as it did for me). Multiple microphones are built into our phones, laptops, smart speakers, hearing aids, smart headphones, audio conferencing equipment, and so much more. For example, the Amazon Echo has seven microphones and the Microsoft Kinect has four. These microphone arrays use subtle time-of-flight differences between signals at different sensors to determine what sounds are coming from what directions, track them as they move, and separate the signals spatially.

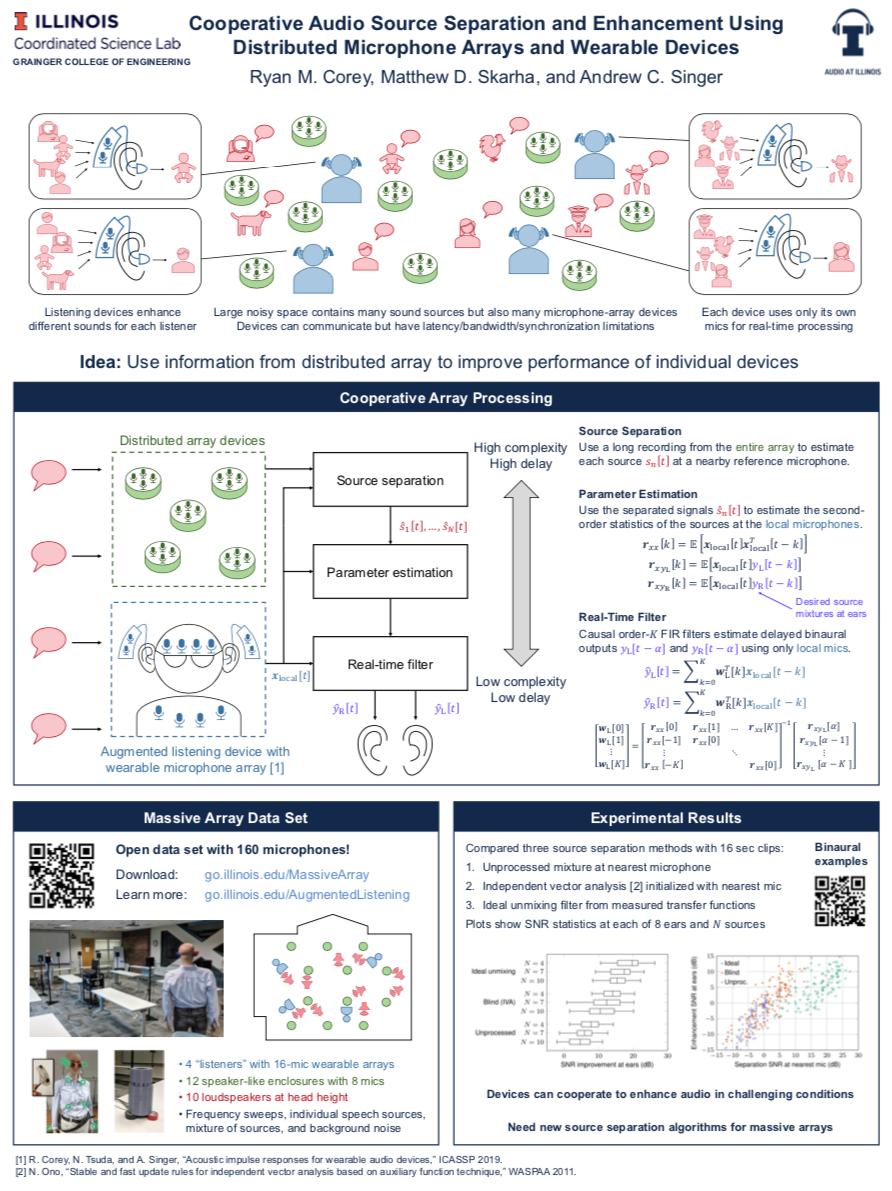

In our proposed system, we used similar techniques to perform source separation by exploiting the redundancies of all the microphones in a given room. The source separation system, which would run on a powerful computer or the cloud, decides what sources are in the room, where they are, and how sound propagates from the sources to each user’s listening device. Then, each listening device uses this information to design its own beamformer that uses only its own nearby microphones. Beamformers are like flashlights but instead of emitting light in the form of a beam, we are collecting acoustic information for a given three-dimensional space.

Implementation

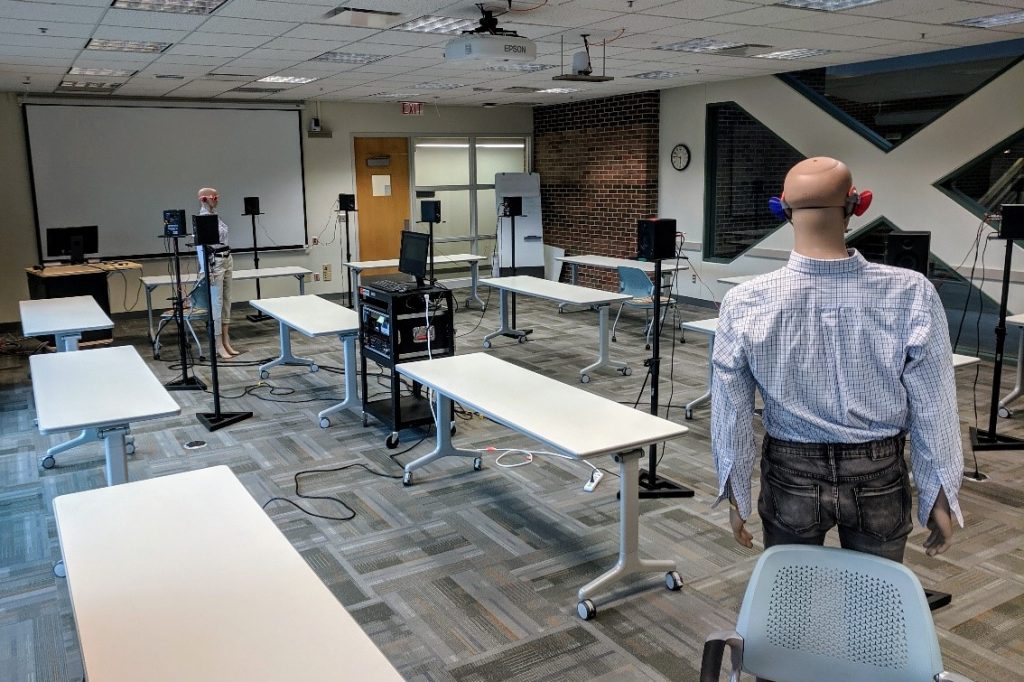

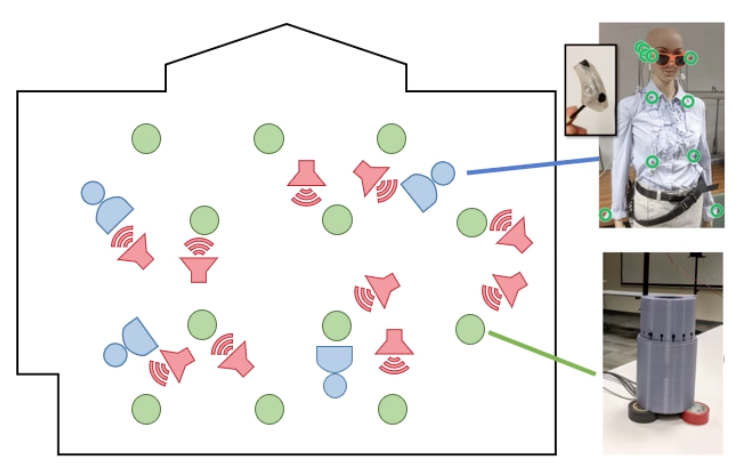

To test the proposed system, Ryan and I filled a medium-sized conference room with 160 lavelier microphones. There were four mannequins with 16 microphones mounted at various locations on their clothes (Ryan did some other work on wearable microphone arrays) as well as 12 enclosures that simulated smart speakers distributed around the room that each had eight microphones. Ten loudspeakers were mounted roughly at head height to simulate a cocktail party scenario.

We recorded both impulse responses (to learn about the room acoustics) and speech samples played at each of the ten speakers, as well as a mixture of the speakers to simulate a cocktail party scenario. The work resulted in a CAMSAP paper, poster (below) and publicly-available dataset. Check out some of the results on our demos page.

A Word on Privacy

Obviously, there are severe privacy concerns that have not been addressed in this work. For starters, a user would be able to listen to any sound source, even if it is on the other side of the room. Furthermore, a hacker would be able to hijack the contents of any conversation in a room for whatever purpose. Luckily, a great deal of research has been done into privacy-preserving inference algorithms (see Peter Kairouz’s Ph.D. thesis) where the algorithm could perform acoustic channel estimation without having direct access to the signal’s content. That is, there are ways of encrypting signals in a context such as an audio remixing system that would allow them to protect user privacy. Nonetheless, more research needs to be done into the appropriateness for such a system in a given context and its impact on user privacy before being implemented in a real-world setting.

(C:)

(C:) projects

projects Performance Tradeoffs in HRTF Interpolation Algorithms for Object-Based Binaural Audio

Performance Tradeoffs in HRTF Interpolation Algorithms for Object-Based Binaural Audio